Historical Tales | News | Vampires | Zombies | Werewolves

Virtual Academy | Weapons | Links | Forum

|

|

Historical Tales | News | Vampires | Zombies | Werewolves Virtual Academy | Weapons | Links | Forum |

Return to Werewolf Biology

|

| A werewolf den in Georgia; 1944 |

Werewolf dens are snug—typically 10 to 12 feet long and a few feet high. They keep a clean, simple home, with bedding from plant materials, feathers and down. Although their coat thickens in response to cold weather, they can and will skin animals for blankets.

Interestingly, werewolves often hold on to items that meant something to them during their human existence: pictures, jewelry, souvenirs, clothing, books, etc. But for the most part, their living standards are closer to those of their wolf cousins than of humans.

|

|

The back feet and front paws of a werewolf are double the size of their former human appendages. They also tend to be larger than bear tracks, with the digits arranged in a more pronounced arc. |

Like most humans, werewolves are quite attentive to their hygiene: they enjoy frequent baths in lakes and rivers, and will even rake their claws through their fur like a comb. They also chew certain plants to create crude poultices for wounds they receive taking down large prey.

Because of their remarkable intelligence and adaptability compared to common animals, werewolves can survive virtually anywhere, from the coldest polar regions to the hottest tropical rainforests. A single werewolf's home range is typically several hundred square miles. Being omnivorous, they spend much of their time hunting and foraging, eating anything and everything from berries and plants to fish, rodents and even large ungulates such as elk and moose.

As with bears, werewolves can fatten up and hibernate for up to several months without eating, drinking, urinating or defecating. Unlike vampires and zombies, however, werewolves cannot survive being frozen.

|

That is not to say that werewolves never hunt humans: the Beast of Gévaudan killed more than 80 people in 1760s France, and a series of werewolf attacks on fishing camps and small towns in Wisconsin during the 1920s resulted in 23 deaths. The latter wolfman was killed by a team of FVZA agents, and the subsequent autopsy revealed a viral infection in its brain, suggesting that it may have been suffering from derangement. Werewolf attacks on humans are also associated with droughts and other situations that might put the beasts under stress. However, this is not a common phenomenon, considering their adaptability.

Although werewolves are highly territorial and easily threatened, their resulting behavior is largely situational. For instance, a single hiker blundering into their range might be shadowed for a while and then left alone, while a party of armed hunters is far more likely to incite their wrath. If you wish to avoid becoming prey, do not travel in deep woods during the sunrise and sunset hours. Firearms will just agitate the wolfman and are not going to be of much help if it attacks. But rest assured: werewolf attacks are extremely rare, and should not dissuade anyone from enjoying recreational activities such as camping and hunting.

|

|

Photo of a werewolf that had broken into a Canadian couple's cabin |

Females tend to behave quite differently, as they don't seem to mind sharing the same land, and will sometimes even work together in the absence of a male.

Male and female werewolves get along especially well: once contact is made, they will spend the next several days together, hunting, frolicking and mating. Once the female is pregnant, however, the male usually leaves. Still, long-term bonds aren't unheard of.

After a nine-month gestation, the female will give birth to a single pup. Though pink, hairless and only a pound or so at birth, the pup grows quickly, reaching adult size in just two years. It will accompany its mother until then, before being expelled into the wild to survive on its own. For reasons not entirely clear, a female werewolf can only give birth once in her lifetime.

At adulthood, the differences between born werewolves and turned werewolves are very subtle: the latter seem to have more stretch marks on their epidermis, and a more jagged shape to their growth plates. Still, it's far from an exact science. A more obvious way to tell is if the werewolf has tattoos, piercings, surgical scars or a missing foreskin.

|

|

The remains of werewolf killed in a mudslide in southern California; 1986 |

|

| A dessicated werewolf carcass in Alaska |

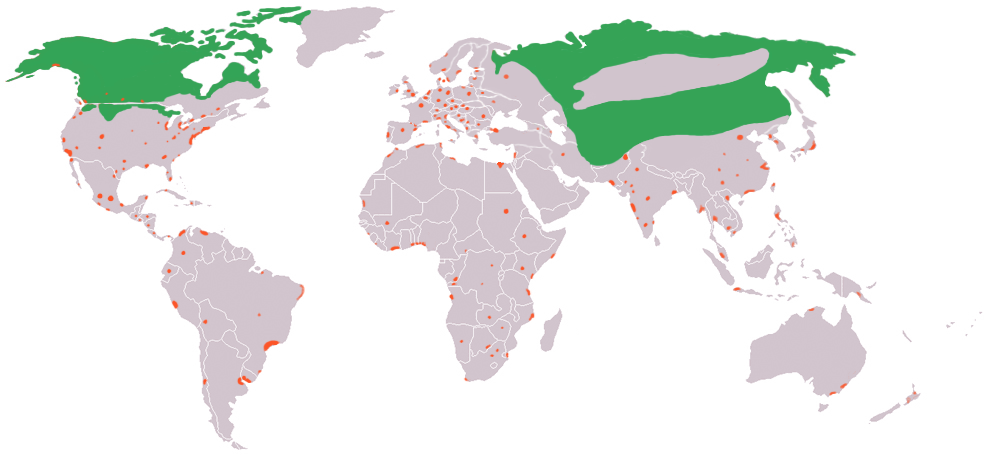

As for population, the number of werewolves in existence is probably less than 1000 worldwide, as development has encroached significantly on their habitat. Werewolf distribution is closely linked with that of their wolf cousins, and are predominantly found across North America, Europe and Asia. Canada is likely home to the largest number.

|

| Global distribution of werewolf habitats, marked in green |

|

|

Werewolves were typically kept in large bear cages. |

Attempts have been made to try to keep werewolves alive by sedating them and inserting a feeding tube, but even the highest dosages have little effect on their will to die.

Early-stage LPV victims tend to last somewhat longer in captivity, but only by a week or so—as proven by the Soviets in their attempts to create more werewolves.