Historical Tales | News | Vampires | Zombies | Werewolves

Virtual Academy | Weapons | Links | Forum

|

|

Historical Tales | News | Vampires | Zombies | Werewolves Virtual Academy | Weapons | Links | Forum |

Return to Werewolf Virology

|

|

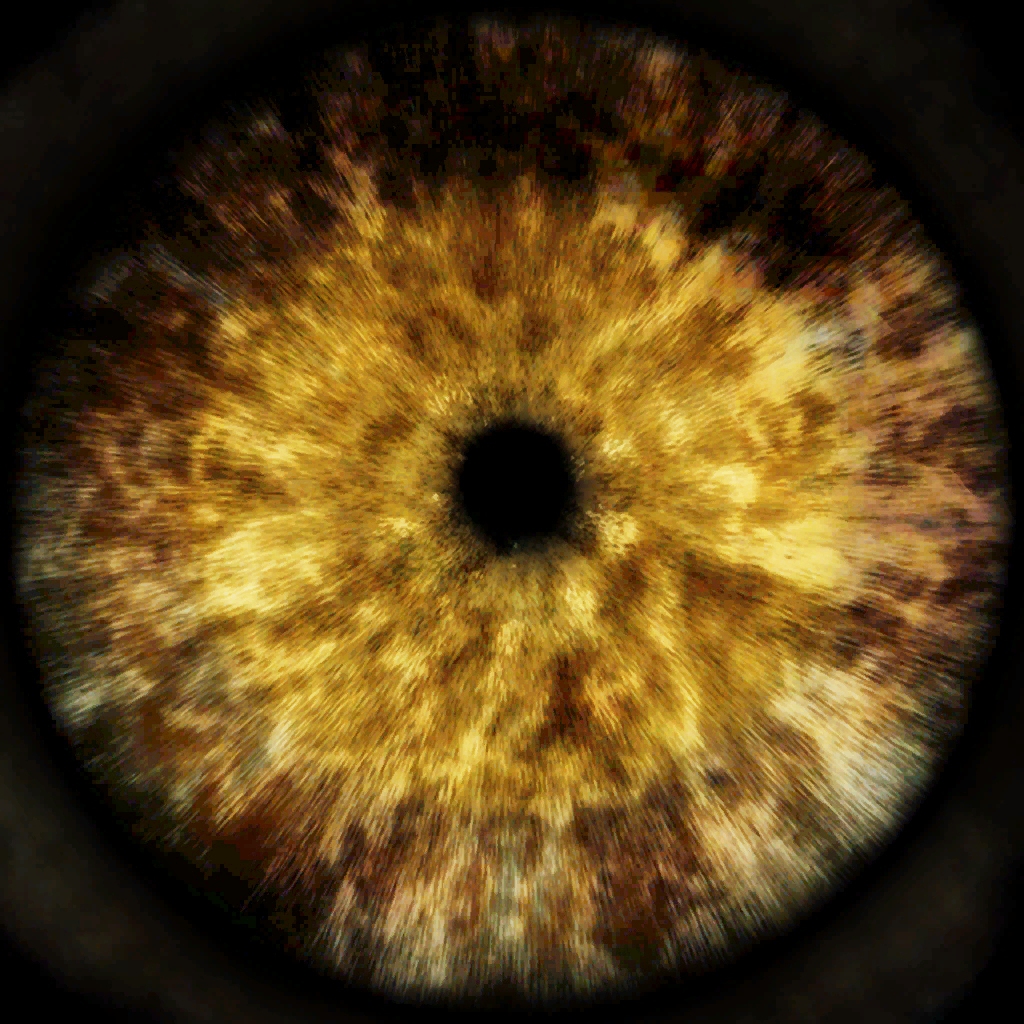

High-resolution photo of a lycanthropic eyeball |

Sight: Besides appearing irritated and bloodshot, the first thing to happen to the eyes is the formation of tapetum lucidum tissue behind the retina, causing eyeshine and improved night vision. Afterwards, as the inflamed sclera darkens to a more brownish or black tone, loss of pigment in the iris brightens its hue to either a pale icy blue or an intense yellow/amber coloration. Finally, the iris and cornea will slowly expand to take up more of the eyeball's surface, making the pupils appear smaller.

Smell/Hearing: For an early werewolf, hearing range quickly triples to that of a vampire, while smell becomes as keen as a zombie's. As these senses further sharpen, cartilage production causes the nose and ears to swell and enlarge, with the former becoming wider and flatter and the latter more pointed and raised. Eventually olfaction becomes 100 times keener than that of a human, while hearing ends up quadrupled.

|

|

This screencap from An American Werewolf in London accurately captures the look of an early-stager. |

Hair/Skin:

The first thing the victim will experience is an increase in body and facial hair, much like those who suffer from hypertrichosis. As it becomes coarser and thicker over the following days, the hands, feet and face become bruised and swollen as if they had been severely beaten. Soon this swelling and bruising spreads across the rest of the body as the victim experiences new bone growth. Like bears and other large mammals, an increase in melanin turns the skin either a very light or very dark grey, depending on the victim's ethnicity. However, the eyelids, nose, lips, soles and palms always become dark and thick, while the breasts and genitals remain somewhat lighter in color. The hair on the scalp is gradually shed as a sort of frizzy mane grows from the head, neck, back and chest. Unlike wolves, werewolves do not have whiskers.

|

| Early tail formation |

Sweat Glands:

As the victim grows more body hair, they lose most of their ability to sweat everywhere except their palms and soles. Like wolves and other mammals, werewolves cool off mainly by breathing and panting, as fluid evaporation cools the blood vessels of the lungs and tongue. Sweating also occurs around the nose, though moisture is usually the result of fluid from the nasal mucosa. Although these areas are usually dry, additional excess heat is released through the ears, face, shoulders and inner thighs thanks to the sparser hair and thinner skin. Apocrine glands also release sweat into the hair follicles, but these are mostly just used to deliver pheromones.

Anal Glands/Tail:

Like many mammals, including dogs, cats and even humans, werewolves bear a small gland on either side of their anus between the external and internal sphincter muscles. These glands secrete a foul-smelling liquid that is used to identify other werewolves and mark territory. Elongation of the coccyx into a fully functional tail seems to aid in this practice, and is around a foot long with sparser and shorter fur than that of a wolf.

Nails/Limbs:

As the hands and feet swell and bruise, the nails on the serum-glazed fingers and toes come loose and soon fall out as the distal phalanx bones grow into hooked claws, which slowly erupt from the former nail beds as hard keratin forms around the new quicks. Starting off short and small, these claws can grow to over six inches long, with tangible girth and thickness. Eventually a werewolf's hands become more like bear paws, limiting the use of their thumbs while making it easier to dig and move on all fours. Elongation and thickening of the forearms, feet and spinal column occur soon after for this purpose.

|

|

Doubling in size, this is what ultimately becomes of the hands. |

|

|

Werewolf feet are generally plantigrade during bipedal movement, and digitigrade while on all fours. |

|

|

Bad Moon's accurate rendition of a fully-transformed werewolf |

|

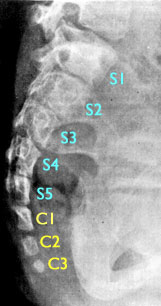

| Two open growth plates |

Growth Plates: As a person grows, cartilage-bound fractures in the skeleton allow enlargement and lengthening of the bones. But once adulthood is reached, these fractures ossify into solid bone, preventing any further growth. So how are werewolves able to bypass this natural restriction? Three cell types are involved in the reversal of this ossification: osteoclasts, which break down bone tissue by dissolving its mineralized matrix (a process known as bone resorption); chondrocytes, which form new cartilage to replace the missing bone; and fibroblasts, which strengthen the cartilage by reinforcing it with additional collagen. Once this process is complete, cartilage can once again stack inside the open growth plates and spread across the outside of the skeleton to form new bone tissue via osteoblasts, which replace old cartilage as it degenerates. This continues until a few years after transformation, when cartilage production stops and the plates once again ossify into solid bone.

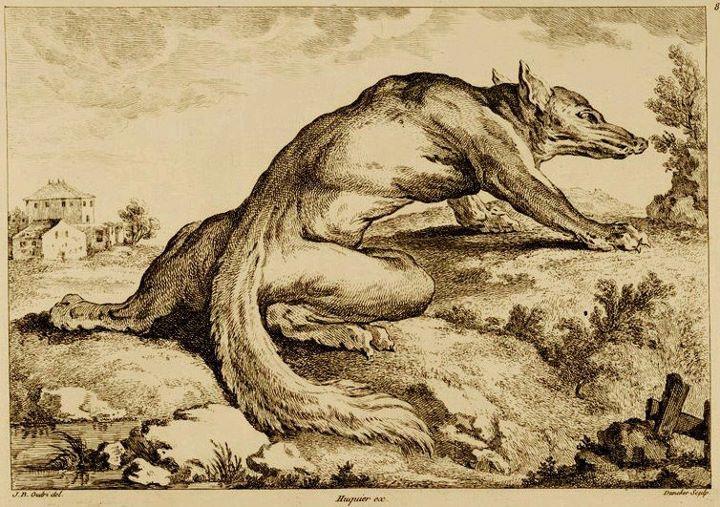

Skeletal System: Skeletally, werewolves have more in common with large bears than they do with wolves, with the following differences from the former: the eye sockets and cranium are more ape-like with a similar attachment point to the spine, the upper torso is somewhat shorter with wider shoulders and intact clavicles, the pelvis is larger and wider with a longer tail, the hind legs and feet are more elongated, and the five digits on each paw and foot are arranged in a wolf-like arc. The average height for a fully-grown werewolf ranges from 7 to 9 feet tall when standing on their hind legs, and they can weigh close to 1000 pounds. Both height and weight depend on pre-transformation factors (as do fur and eye color), along with nutritional intake during and after the transformation.

|

|

An old, semi-accurate illustration of a werewolf's body structure |

Medical Applications:

It's believed that the deossification process in lycanthropic growth plates inspired Italian surgeon Alessandro Codivilla to try this himself, resulting in a surgical practice during the early 1900s known as distraction osteogenesis. This process is used to reconstruct skeletal deformities and lengthen the long bones of the body by cutting the bone in two and allowing new bone tissue to form in the gap, which is gradually moved apart until the desired length is reached. Not only does it lengthen bone tissue, distraction osteogenesis also has the benefit of simultaneously increasing the volume of surrounding soft tissues. This surgical practice is perhaps best known for reversing the effects of dwarfism, and it's hoped that in the future a more natural process can be used to turn ossified growth plates back into cartilage. But alas, only werewolves are capable of this for now.

|

|

Human heart (L) compared with a lycanthrope's (R) |

|

| The carcass of a wolf had succumbed to LPV |

Because their cellular makeup is so different from humans, the lycanthropy virus seems to have no effect whatsoever on vampires or zombies. Fully-transformed werewolves infected with vampirism or zombism would most likely become rabid and die like other non-human mammals, although this scenario has never been tested or observed; and the data on early-stage werewolves is insufficient.

|

|

How the Soviet Strigoi probably looked |

That's not to say that a vampirolycanthrope isn't possible—if the fast-acting vampirism virus was injected into a human roughly 24-48 hours after being infected with the slow-acting lycanthropy virus, so that not every cell is transformed by one or the other. And because the resulting tissues will be mismatched, the host would also have to be administered cortisone (or a similar drug) to suppress its immune system.

A Soviet experiment during the 1950s used just this method on an unknown number of criminals and political prisoners through cruel and vigorous trial and error. Of course, most of them either died or became vampires—except for one man, a 30-year-old thespian who transformed over the next few weeks into a creature that looked somewhat more humanoid than a typical werewolf, but with all the undead features of a vampire. The Soviets dubbed this hybrid the "Strigoi," after the shapeshifting vampires of Romanian mythology. What happened to this being is unknown, as most of the records on it were either withheld or destroyed.