Historical Tales | News | Vampires | Zombies | Werewolves

Virtual Academy | Weapons | Links | Forum

|

|

Historical Tales | News | Vampires | Zombies | Werewolves Virtual Academy | Weapons | Links | Forum |

Women played a vital and often unsung role in the development and success of the FVZA. In fact, the agency was more progressive with respect to women's roles than were other areas of law enforcement and the military, primarily because of the pressing need for qualified personnel stateside during wartime.

|

| Early nursing class at Fort McNair. |

Women served mostly in clerical roles at FVZA offices in the early days of the agency. In 1894, a nursing institute was founded at Fort McNair in Washington, D.C., to provide specialized training for women in zombie and vampire medicine. At that time there was no vaccine for either condition, so treatment was mostly palliative. The nurses learned to recognize and distinguish between the signs of vampire and zombie infections and how to restrain bite victims and make them more comfortable. They were also tasked with the very difficult work of euthanizing bite victims.

After the zombie vaccine was developed, nurses took on a more prominent role in the agency. They raced about in specially outfitted Model T automobiles trying to get injections to victims within the short window of time when the vaccine would work. It was a dangerous job, complicated by poor roads and primitive communications technology. All too often, nurses would arrive at a location to find that the bite victim had already transformed. Dozens gave their lives in service during the years before World War II.

Despite their accomplishments, women were forbidden from service as FVZA agents for the first half of the twentieth century. Agency leaders figured the public would have little appetite for hearing about females being killed in the line of duty. Still, some women were brought in to assist with investigations, as experienced investigators found that female prostitutes, a major target for vampires, tended to be more forthcoming when speaking with other females.

|

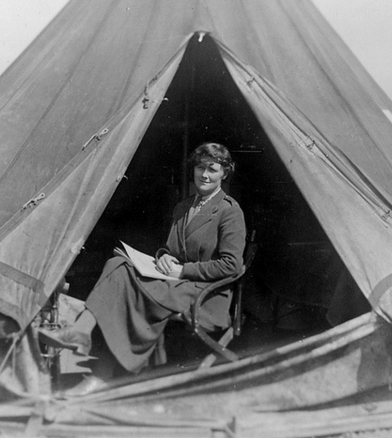

| Marion Southwick in Saipan, 1945. |

The prohibition against women agents ended largely as a result of World War II, when FVZA leaders created the Vanguard Women's Auxiliary Corps (V-WACS) to assist soldiers in Europe and the Pacific. One of the first volunteers was Marion Southwick, a native of Maine who served in the Pacific theater, where zombie outbreaks were not unusual. While on duty on the Pacific island of Saipan in 1945, she reportedly gunned down four zombified Japanese soldiers who had burst out of a cave when an army unit was passing by. While some may have been scarred for life by the encounter, Southwick was exhilarated. When she returned home, she lobbied for a position as an agent, biding her time by authoring a training manual especially for the V-WACS.

Southwick finally got the call in 1949. Married and with one child at the time, she trained in New York City, where she faced an entrenched "Old Boys" network and some outmoded ways of thinking. The Special Agent in Charge said of her, “This lady is perhaps too refined to work on investigations.” He advised that she should only be assigned to open cases that “weren’t too rough.”

Southwick persevered through training and was appointed to an investigative unit by FVZA Director William Burns on October 11, 1950. She was assigned to the Washington D.C. office, where she made $7.50 a day for service in “the Investigation of Vampires and Zombies.” This was some 20 years before the Federal Bureau of Investigation accepted its first woman.

Inspired by Southwick's example, many women served with distinction in the final decades of the Agency's existence. Several female scientists played important roles on the Zozobra Project, the effort to find a vaccine to the virus that causes vampirism, and were involved on investigative units, assault teams and as as Shadows. Southwick herself rose to the position of Assistant Director in 1970, five years before the FVZA was disbanded.