Historical Tales | News | Vampires | Zombies | Werewolves

Virtual Academy | Weapons | Links | Forum

|

|

Historical Tales | News | Vampires | Zombies | Werewolves Virtual Academy | Weapons | Links | Forum |

Note from Dr. Pecos: Here is my original page on the vampirism virus, with text and format edits by Robert Lomax. To view his extended pages, click here.

In 1616, Italian scientist Ludovico Fatinelli published his Treatise on Vampires, in which he speculated that vampirism was caused by a microscopic pathogen. Tragically, he was burned at the stake for heresy, but his research lived on to inspire countless dedicated men and women to bring you the information included on this page.

|

|

HVV carrier: vampire bat |

|

|

HVV source: the bat flea Ischnopsyllus elongatus |

While most viruses are highly specific in what tissues they target, HVV is able to infect every living cell in the body, with the exception of red blood cells (which are replaced over time by the infected bone marrow). It's also much less destructive, as it can effectively transform tissues without causing cancer or necrosis.

While in theory HVV infection is possible through any exchange of bodily fluids, transmission occurs through the bite of an infected person or animal in virtually every case. Thankfully, the virus isn't airborne, and waterborne transmission is highly improbable.

|

|

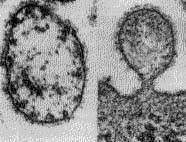

Electron micrograph of HVV (L). The virus budding off an infected cell (R). |

Stage One: Infection

Within six to twelve hours of exposure, the victim develops a headache, fever, chills and other flu-like symptoms—as well as a drastic increase in metabolism and cardiac output as the virus spreads throughout the body. These symptoms can be easily confused with more common infections, although the presence of bite wounds is usually enough to confirm the diagnosis. This stage generally lasts another six to twelve hours, during which the vaccine is over 98 percent effective. The victim should also be treated with fluids and antibiotics to prevent dehydration and secondary infections.

|

|

In 1800s France, an infected woman is given a transfusion of goat's blood—a desperate, futile measure to ward off the disease. |

Stage Two: Coma

Within 24 hours of exposure, the victim will slip into a vampiric coma. About 10 hours into this phase, the pulse slows, breathing is shallow and the pupils are dilated. Thousands have been buried alive because of this. While it is commonly believed that anyone infected with HVV turns into a vampire, in fact only a small percentage of people survive vampiric comas. Generally, the young, old and feeble never come out of their comas and eventually die, while the vast majority of survivors are males between the ages of 18 to 35. For the latter group, vampiric comas last about a day and typically end at night, but the former demographic may linger for an additional day or so before death. The vaccine is roughly 50 percent effective when administered during the first half of this stage: the longer the coma has passed, the less effective the vaccine.

|

|

During vampirism epidemics, many victims were buried while still in a vampiric coma. |