Famous Cases | Historical Tales | Vampires | Zombies

|  |

Famous Cases | Historical Tales | Vampires | Zombies |

|

![]() Luby's seems an unlikely place to find the wealthiest man in the state of New Mexico, but at 5:30 p.m. sharp, Clarence Ragsdale appears in all his glad-handing, back-slapping glory. If the great man, worth an estimated $3 billion, is embarrassed by the humble surroundings, he hardly shows it. The soporific muzak playing on dining room speakers is no match for his basso profundo voice.

Luby's seems an unlikely place to find the wealthiest man in the state of New Mexico, but at 5:30 p.m. sharp, Clarence Ragsdale appears in all his glad-handing, back-slapping glory. If the great man, worth an estimated $3 billion, is embarrassed by the humble surroundings, he hardly shows it. The soporific muzak playing on dining room speakers is no match for his basso profundo voice.

![]() As I watch this portly 60-year old in Wranglers and shit-kickers cross the room, two things occur to me: one, all the money in the world can't buy a good hairpiece; and two, it's easy to see why the man never lost an election in New Mexico. He truly seems to enjoy kissing babies and lending a sympathetic ear to disgruntled old-timers. It takes him 30 minutes to reach my table.

As I watch this portly 60-year old in Wranglers and shit-kickers cross the room, two things occur to me: one, all the money in the world can't buy a good hairpiece; and two, it's easy to see why the man never lost an election in New Mexico. He truly seems to enjoy kissing babies and lending a sympathetic ear to disgruntled old-timers. It takes him 30 minutes to reach my table.

![]() Not that I expected him to hurry over. As a Congressman, Ragsdale generally put the media somewhere between pornographers and child molesters on the food chain. But now, he needs the press as he lobbies Congress for approval of the right to test a longevity drug made from altered vampire DNA on animals. Which explains why he made the four-hour drive from his enormous ranch in southern New Mexico to meet me at what he jokingly calls his "Albuquerque office."

Not that I expected him to hurry over. As a Congressman, Ragsdale generally put the media somewhere between pornographers and child molesters on the food chain. But now, he needs the press as he lobbies Congress for approval of the right to test a longevity drug made from altered vampire DNA on animals. Which explains why he made the four-hour drive from his enormous ranch in southern New Mexico to meet me at what he jokingly calls his "Albuquerque office."

|

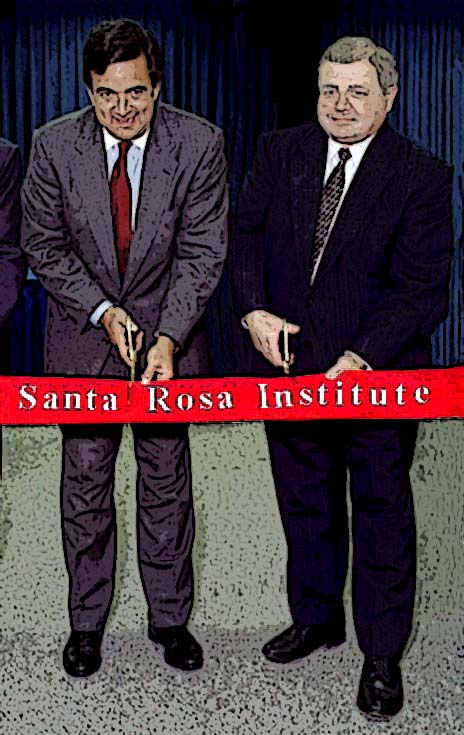

| Ragsdale (r) and New Mexico Congressman Bill Richardson at the opening of SRI's new research center |

![]() That meeting took place when Ragsdale spent a couple of weeks at Dr. Edward Westhead's now defunct Gerontology Center, a spa-cum-research center in Santa Fe that stressed a New Age regimen of diet, exercise and meditation. "I had beaten the cancer," he says, "but I knew I had to change my lifestyle. Dr. Westhead showed me the way." The two men became fast friends. Ragsdale says it was Westhead who alerted him to both the potential and the mismanagement at the Santa Rosa Institute. Two years later, Westhead was in charge at the Institute and Ragsdale was on the Board of Directors. The Methuselah Project began shortly thereafter.

That meeting took place when Ragsdale spent a couple of weeks at Dr. Edward Westhead's now defunct Gerontology Center, a spa-cum-research center in Santa Fe that stressed a New Age regimen of diet, exercise and meditation. "I had beaten the cancer," he says, "but I knew I had to change my lifestyle. Dr. Westhead showed me the way." The two men became fast friends. Ragsdale says it was Westhead who alerted him to both the potential and the mismanagement at the Santa Rosa Institute. Two years later, Westhead was in charge at the Institute and Ragsdale was on the Board of Directors. The Methuselah Project began shortly thereafter.

![]() When it comes to the Methuselah Project, Ragsdale has no patience for his opponents, especially Dr. Hugo Pecos. "I understand where he's coming from," he says. "Poor sonofabitch lost his brother to vampires. But come on, friend, the war is over. I mean, he's like one of those Japanese soldiers they drug out of a cave twenty years after World War II ended." With that, Ragsdale begins running down the same well-rehearsed arguments I heard earlier from Dr. Westhead. If we don't do it, someone else will, safety is our top priority, etc., etc.

When it comes to the Methuselah Project, Ragsdale has no patience for his opponents, especially Dr. Hugo Pecos. "I understand where he's coming from," he says. "Poor sonofabitch lost his brother to vampires. But come on, friend, the war is over. I mean, he's like one of those Japanese soldiers they drug out of a cave twenty years after World War II ended." With that, Ragsdale begins running down the same well-rehearsed arguments I heard earlier from Dr. Westhead. If we don't do it, someone else will, safety is our top priority, etc., etc.

![]() Ragsdale won't disclose how much of his own fortune he has invested in the Methuselah Project, but he will readily admit to a selfish interest in the work. "I'm a lot older than you, son. There's so much more I want to do." When I remind him that, optimistically, it will be 25 years before a drug is ready for use, he doesn't bat an eye. "I think if this (animal testing) part of the research shows results, we'll be able to move that timetable up."

Ragsdale won't disclose how much of his own fortune he has invested in the Methuselah Project, but he will readily admit to a selfish interest in the work. "I'm a lot older than you, son. There's so much more I want to do." When I remind him that, optimistically, it will be 25 years before a drug is ready for use, he doesn't bat an eye. "I think if this (animal testing) part of the research shows results, we'll be able to move that timetable up."

![]() After spending an hour with him, I can see that Ragsdale is the Institute's greatest asset, and it's not just because of all the money he's kicked in. The fact is, the man could sell sand to a Bedouin. He has lined up important allies in Congress. Hell, after an hour with him, I'm ready to invest. "In my lifetime," he says, voice rising, "I've seen men cure polio, discover a vampire vaccine and walk on the moon. So there is no reason, if we put our heads together, we can't crack this nut." If Ragsdale sounds evangelical, it's no accident: he sees the Methuselah Project as the realization of a sort of divine imperative. "Think about it," he says. "God put vampires on this earth to test us. And hidden in the solution to that test was our salvation. Immortality."

After spending an hour with him, I can see that Ragsdale is the Institute's greatest asset, and it's not just because of all the money he's kicked in. The fact is, the man could sell sand to a Bedouin. He has lined up important allies in Congress. Hell, after an hour with him, I'm ready to invest. "In my lifetime," he says, voice rising, "I've seen men cure polio, discover a vampire vaccine and walk on the moon. So there is no reason, if we put our heads together, we can't crack this nut." If Ragsdale sounds evangelical, it's no accident: he sees the Methuselah Project as the realization of a sort of divine imperative. "Think about it," he says. "God put vampires on this earth to test us. And hidden in the solution to that test was our salvation. Immortality."

![]() It's seven-thirty now and the restaurant's senescent clientele has largely cleared out. I follow Ragsdale out of the air-conditioning and the muzak and into the parking lot, which is lit by a spectacular, salmon-pink sunset. "I never get sick of this view," he says, heaving himself into a Brobdingnagian pickup truck. And then he drives off into that sunset, enjoying the fleeting glory of it before everything goes black.

It's seven-thirty now and the restaurant's senescent clientele has largely cleared out. I follow Ragsdale out of the air-conditioning and the muzak and into the parking lot, which is lit by a spectacular, salmon-pink sunset. "I never get sick of this view," he says, heaving himself into a Brobdingnagian pickup truck. And then he drives off into that sunset, enjoying the fleeting glory of it before everything goes black.

![]() I had come to Albuquerque to try and get to the bottom of the conflict over the Santa Rosa Institute and the Methuselah Project. I wanted to find out who was right and who was wrong, but I've come to the conclusion that right or wrong has nothing to do with it. Vampires are immortal, and people want to know why, people driven by that same curiosity that led Pandora to open the box so long ago. In a way, the Methuselah Project is the ultimate American endeavor. The quest for eternal youth, fueled by scads of money and relentless optimism; unbridled capitalism turned loose on the last frontier of medicine. And what better man to conquer that frontier than Clarence Ragsdale, descendant of the breed that traveled out here in wagons, subdued the savages, paved paradise and put up a parking lot. Still, as my plane leaves Albuquerque the next morning, I can't help but think of the gruesome artifacts on display in a faroff corner of the Santa Rosa Institute. Seeing the macabre remains makes it easier for me to understand the mixture of fear and revulsion in Dr. Pecos' eyes when he spoke of the day he saw his brother dragged away by vampires. That kind of fear is alien to me, and I can only hope it stays that way.

I had come to Albuquerque to try and get to the bottom of the conflict over the Santa Rosa Institute and the Methuselah Project. I wanted to find out who was right and who was wrong, but I've come to the conclusion that right or wrong has nothing to do with it. Vampires are immortal, and people want to know why, people driven by that same curiosity that led Pandora to open the box so long ago. In a way, the Methuselah Project is the ultimate American endeavor. The quest for eternal youth, fueled by scads of money and relentless optimism; unbridled capitalism turned loose on the last frontier of medicine. And what better man to conquer that frontier than Clarence Ragsdale, descendant of the breed that traveled out here in wagons, subdued the savages, paved paradise and put up a parking lot. Still, as my plane leaves Albuquerque the next morning, I can't help but think of the gruesome artifacts on display in a faroff corner of the Santa Rosa Institute. Seeing the macabre remains makes it easier for me to understand the mixture of fear and revulsion in Dr. Pecos' eyes when he spoke of the day he saw his brother dragged away by vampires. That kind of fear is alien to me, and I can only hope it stays that way.