Famous Cases | Historical Tales | Vampires | Zombies

|  |

Famous Cases | Historical Tales | Vampires | Zombies |

|

| Baron Haussman |

|

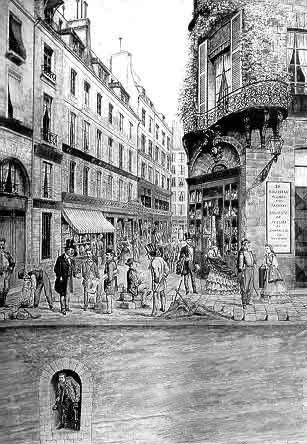

| "What Vampire Problem?" In this sardonic 1913 French illustration, a lone vampire prowls the sewers of Paris, unbeknownst to the passersby above |

European leaders tried a variety of measures to try and control vampire numbers, including hiring more vampire-fighters and instituting strict curfews. But the number of attacks continued to climb. In 1850, Baron Georges Haussman, Paris' top city planner, offered a radical suggestion: instead of trying to kill the vampires, why not eliminate their habitat? Haussman envisioned a radical reconstruction of Paris, with broad boulevards, spacious squares and a modern sewer system (it was still common belief that poor sanitation contributed to vampirism).

Haussman's plan won approval from French Emperor (and Napoleon grandson) Louis Napoleon and, in 1853, work crews began tearing down the Vampire Quarter, building by building. As crowds of onlookers watched, vampires scurried from collapsing buildings, shrieking and shielding their eyes from the sun, only to be methodically destroyed by special legions of the French Army. In one church, more than 50 vampires were flushed from the crypt. While some French, like writer Emile Zola, protested the widespread destruction of architectural treasures and the lack of interim housing for the homeless, the project did seem to be succeeding in slowing the rate of vampire attacks.

|

| In Paris, aging tenements were torn down (l) to make room for the Paris Opera (r) |

However, the canonization of Haussman proved to be premature. After dropping for a short time, vampire attacks in Paris rose to their highest levels ever. To make matters worse, the attacks were no longer confined to Paris' slums. Vampires attacked the well-heeled of the Tuileries, they preyed on students across the river in the Latin Quarter. The great irony of Haussman's work was that, while he had driven vampires from their old haunts, in building Paris' extensive sewer system he had provided them with the perfect place to hide.

For the next 50 years, these vampires, known in Paris as "Haussman's Children," made their home in the sewers, emerging at night for hunting. For a short time, the French stationed troops there, but had to pull out due to high rates of desertion. During World War II, French resistance fighters hiding from the Nazis in the sewers encountered vampires in