Famous Cases | Historical Tales | Vampires | Zombies

|  |

Famous Cases | Historical Tales | Vampires | Zombies |

|

| Quadilla |

Quadilla grew up riding horses and tending goats and sheep on a farm near the Po River in northern Italy. His bucolic upbringing came to an abrupt end at age 16, when a corrupt local priest confiscated his family's property. The evicted family had the distinct misfortune of settling in a gypsy camp shortly before it was set upon by a small vampire army. Quadilla's parents were killed; he was bitten, then taken away to join the army.

Quadilla quickly distinguished himself as a great horseman and fearless warrior whose ambitions outpaced the limited scope of his precursors. Quadilla envisioned himself as the leader of a vampire empire stretching from Gibraltar to the Danube. With his great skills as an orator, Quadilla was able to convince local vampire armies to join his cause. After winning important victories against the Lombards, the army began a slow, inexorable march down the Italian peninsula toward Quadilla's ultimate goal: the papal leadership in Rome.

|

| Charlemagne |

In December of 772, Quadilla's army took Siena, leaving it only 150 miles from Rome. As the Italian capital swelled with refugees, the stories of Quadilla took on an outsized, mythological scale. Eyewitnesses told of a ten-foot-tall, fire-breathing man with horns, cloven hoofs and a tail. While none of these stories were true, they surely unnerved Pope Hadrian II. The Pope, facing desertions in his own army, sent envoys to the Frankish Kingdom of the north to ask the young king Charlemagne for help.

|

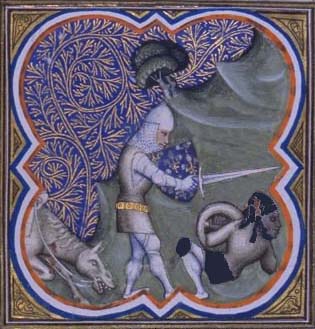

| Charlemagne slays Quadilla (from illuminated manuscript) |

In the spring of 773, Charlemagne led his army across the Alps into Italy. He followed the coast south and made camp along the Tiber River north of Rome, not far from the site of Quadilla's most recent assault. Charlemagne had planned to use the camp as a base from which to conduct sorties into the mountains, but Quadilla had different ideas. That night, the vampire army attacked the camp and inflicted heavy losses on Charlemagne's army before retreating back to their caves.

|

| Charlemagne's fire cart, seen in this medieval illustration, outlived him by almost 1000 years |

Working from cave to cave, it took four days for Charlemagne's army to kill the last of the vampires. Quadilla himself fought gallantly; though effectively rendered blind by the bright sun, he killed over 20 soldiers before Charlemagne dispatched him with a blow from his sword.

On Christmas Day, 773, a grateful Pope crowned Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor in the city he had saved. During Charlemagne's 47-year reign, Europe enjoyed a relative respite from vampire armies. The fire carts Charlemagne had improvised lasted even longer; they were employed against vampires well into the Eighteenth Century.

In 1974, a team of Italian archaeologists discovered a huge cache of artifacts in caves near the Tiber. Among the finds were armor and weapons bearing the broken cross symbol peculiar to Quadilla's army. A museum was built nearby to house the relics and honor the men who saved the seat of Christianity from a grisly fate.